Good King Wenceslas

2012 was the year I discovered I loved Christmas. Before then, I'd coasted through it, grimly accepting the consumerism, the maximalist decorations, the constant commercials, and irritating music in public spaces. Even bearing my family's Germanic traditions, which included my parents speaking to the Christ-child to discuss my brother's and my behavior, unenthusiastic singing of hymns, the repetitive rereading of the Gospel of Luke.

Like many writers/readers of A Very Sufjan Christmas, I had a teenager's pessimistic outlook on holidays, religion, even family gatherings to an extent. Also like many of you, it was through Sufjan's music that I rediscovered the childish joy of the holiday's love, warmth, and brightness. But this essay isn't about Sufjan; it's about my uncle, illness, forgiveness, and tangentially, a song called “Good King Wenceslas.”

Another tradition on the German side of my family: each December since I was a toddler, we've driven to Connecticut to meet with the families of my father's two sisters and to bake hundreds or thousands of eastern European cookies (non plus ultras, hazelnut moons, vanilla kipferl, even the widely despised bourbon balls, which get baked in great quantities anyway for reasons I'll never understand).

Each December, I have snuck away from the shaping, decorating, and baking to spend time with my favorite uncle. I know I'm not supposed to say that I have a favorite, but I do.

He's a lawyer, very intelligent and very funny, and he loves sharing music with me, and every year I've left his house with several jazz LPs to study on my turntable at home. Each year when I'm there visiting him in Connecticut, we leave the baking for a little while and jump in the car and go bowling, or to a record store, or ice skating at the nearby rink.

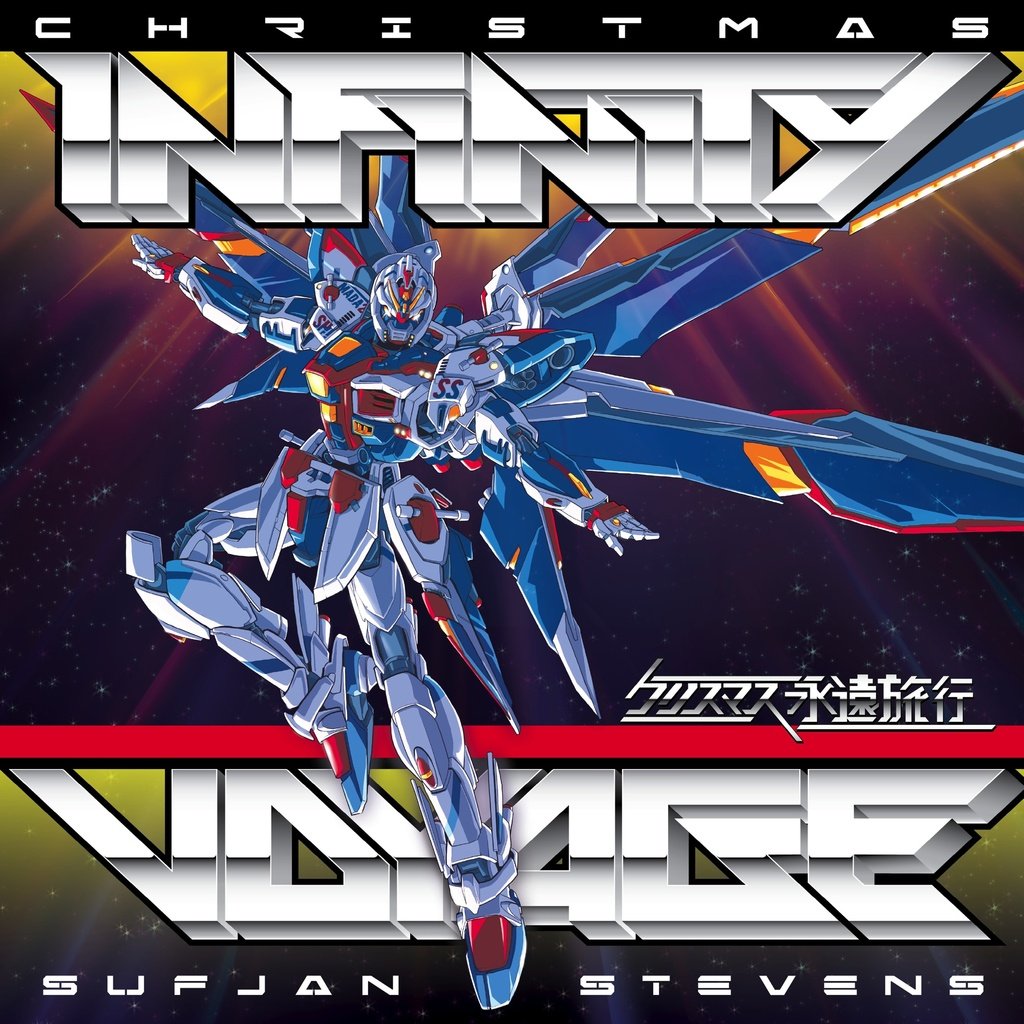

One year I brought Silver & Gold down with me and showed him my favorite track from it, a cyber-psychedelic reimagining of “Good King Wenceslas.” He thought it was hilarious. I know I have more recent memories of his house from the years between then and when I got sick, but that's the one that comes to mind most often now.

My sickness started slowly: walking to a concert in Boston in early 2019, I suddenly felt ill and had to stop. After a while it passed, and I continued.

Later, driving to a restaurant to meet my partner's family, I felt ill again. Like food poisoning, but with a strange dizziness. The certainty that I was on the verge of vomiting, constantly, as long as I was moving. I made it to the restaurant and back. The next day was my partner's sister's school play, which I'd said I would attend, but on the way, I felt ill again, and I went home and waited for it to get better.

Then on a walk with my dad, I had to sit on the ground until he trudged home and came back with a car to pick me up. I stopped going for walks. I got ill on the way to a friend's birthday party. Frustrated, I turned around and went home. I stopped visiting friends.

I missed a trip I'd booked in Montreal with friends. I missed my cousin's wedding in Maryland. A while later, I missed my grandfather's funeral. By then, I wasn't leaving the house to walk or drive. Every time I did, I would feel the same horrible clawing nausea, shortness of breath, dizziness, panic. I'd come to fear this sensation more than anything in the world.

I missed Christmas and the cookie bake. The next year, I missed it again. I’d stayed in touch with my partner, my parents (with whom I lived), and some college friends. I communicated with no one else and only left the house to drive, excruciatingly, to dozens of fruitless medical appointments with clueless specialists. I was diagnosed with Lyme disease, treated with potent antibiotics for eight months, and beat it. My symptoms remained.

I was convinced that I was dying, or already dead, and in some terrible half-dreamt nightmare. I had no social life, went nowhere, and saw no one. I wondered if I were insane, agoraphobic, afflicted with a brain injury.

During this time, I saw my favorite uncle once: he came to my parents' house for a family gathering. He recommended a book called Phantoms of the Brain and suggested I see an ear-nose-throat specialist, and I thanked him and told him I already had, and an inner ear CT scan had shown nothing.

I had little to occupy my time, and although I tried to avoid doing so, I began to tally the many long drives I had made over the years to see friends and family, and I began to obsess over their unwillingness to do the same for me. Some I'd seen once or twice in the two years I'd been sick, some never. I resented them for not reaching out, even though some had, occasionally.

Mostly, I resented my uncle, who I'd loved going to see and spending time with, and who had only come once to our house, and for an unrelated family event to boot. I decided our relationship was predicated on ease — on me making the drive each year to see him, on me enthusiastically going on errands and listening to his music. The last year I went to see him, I had brought a record with me, and he had played me his music until we'd run out of time, and I'd left with the record again, unplayed. I obsessed over this.

I forgot about “Good King Wenceslas” and the record stores and the cookies. It drove me mad that everyone could just forget about me. I was sure I would never do the same in their position, though I had no way of knowing.

There was no moment when I stopped obsessing. In the following order: I got therapy, I got used to being disabled, I found new hobbies and online communities to occupy my time, and then, for no reason, I began to get better. On good days, I went for short walks or drove to the grocery store with my partner. Sometimes I had attacks and had to stop and go back home, and sometimes I made it. Gradually, the ratio changed until I began to feel safe outside again.

It's been nearly three years now since I got ill, and I'm not the vindictive person I was in the darkest moments of my illness. Though I still think about it a lot, I don't know how to quantify what we owe our friends and family: how many yearly visits, how many emails, how many texts and phone calls for those who are living isolated or in difficult circumstances. I feel angry for the years I lost, but I'm no longer angry at my loved ones, none of whom were ever taught some mystical “One True Way” of showing love to one another.

I don't know if it's appropriate to call this forgiveness because I don't think I was wronged, really, by anyone except my body and brain. It seems almost funny now to imagine myself a year and a half ago, huddled in my room, suicidally depressed and having retracted away from everyone in my life, furious that none of them had made an effort that I, too, was unwilling to make.

I continue to improve. I go for walks, and I make short drives. One day I believe I'll drive on a highway again, and maybe I'll make it to Connecticut, and we'll bake some cookies in a warm and familiar house while outside the streets silently fill with snow.

I looked up the lyrics of “Good King Wenceslas,” which I've never paid much attention to. It's about a king who goes on a difficult journey during terrible winter weather to bring food, wine, and firewood to a peasant. The king's page falters during their trek, nearly giving up in the freezing darkness, but sees his master's footprints in the snow and follows them, arriving safely at the peasant's dwelling. I thought that was funny.

Kit Riemer is a writer, photographer, and game-maker from Massachusetts, USA. They are currently writing a text-based game about a poorly programmed AI therapist tasked with keeping a suicidal patient alive. You can see more of their work at their website: interstice.neocities.org.