Break Forth O Beauteous Heavenly Light

It’s Christmas Day, 2003. I rise with the rest of the congregation, eager to lend my voice to one of the two times our songs at Mass are infused with what could be considered happiness, or fun, and belt the opening lines to “Angels We Have Heard On High.” I wear a darling ivory dress, complemented by silk stockings and patent-leather shoes, a mother’s dream. I revel in it. This Mass, I want to stand out - I am a precocious third grader who believes she truly understands the joy and gravity of what Christs’s birth means, and I need everyone to know how seriously I’m taking this. I have three great loves: singing, God, and Harry Potter (but I don’t say that at church.) My adoration is earnest, my faith unshaking, and my voice squeaky, but bold. I make it count because I know all other hymns will be somber until Easter.

***

My current experience of faith is a far cry from my elementary school days of certainty. The older I get, the more fearful I become of the power of the Catholic Church and its insidious teachings. The many ways its abusive love has set the stage for the hardships I’ve encountered since childhood has become steadily clearer over time.

Catholicism taught me about just one woman to emulate, whose defining characteristic and virtue is her virginity. It was not a woman’s role to be a direct line to God; only men could channel that divinity. A woman’s role was to support them.

Catholicism made my bisexuality an impossibility and nightmare, an abomination I was desperate to avoid until I couldn’t ignore it any longer. Catholicism allegedly “hated the sin, but loved the sinner,” and boiled my capacity for love down to a sex act. It named me a deviant.

Catholicism told me repeatedly that I, along with every other human, am inherently bad, and wrong, and will be for the rest of my life. That while I was made in God’s image, I have wretchedness within me. That despite my wretchedness, this just and male God manages to love me, and for that, He is good. That we can never praise Him enough for His goodness and mercy.

Shame was the bedrock on which my faith was founded. I believed that if I felt penitent enough for my badness, I could someday earn God’s love.

In high school, my transition from questioning into outright rejection was swift and devastating. I felt locked out of my own community and was horrified by what I had been forced to internalize. I felt disgust at each Mass, and I stopped taking communion. I skipped most lines of the Apostle’s Creed. But I still sang.

***

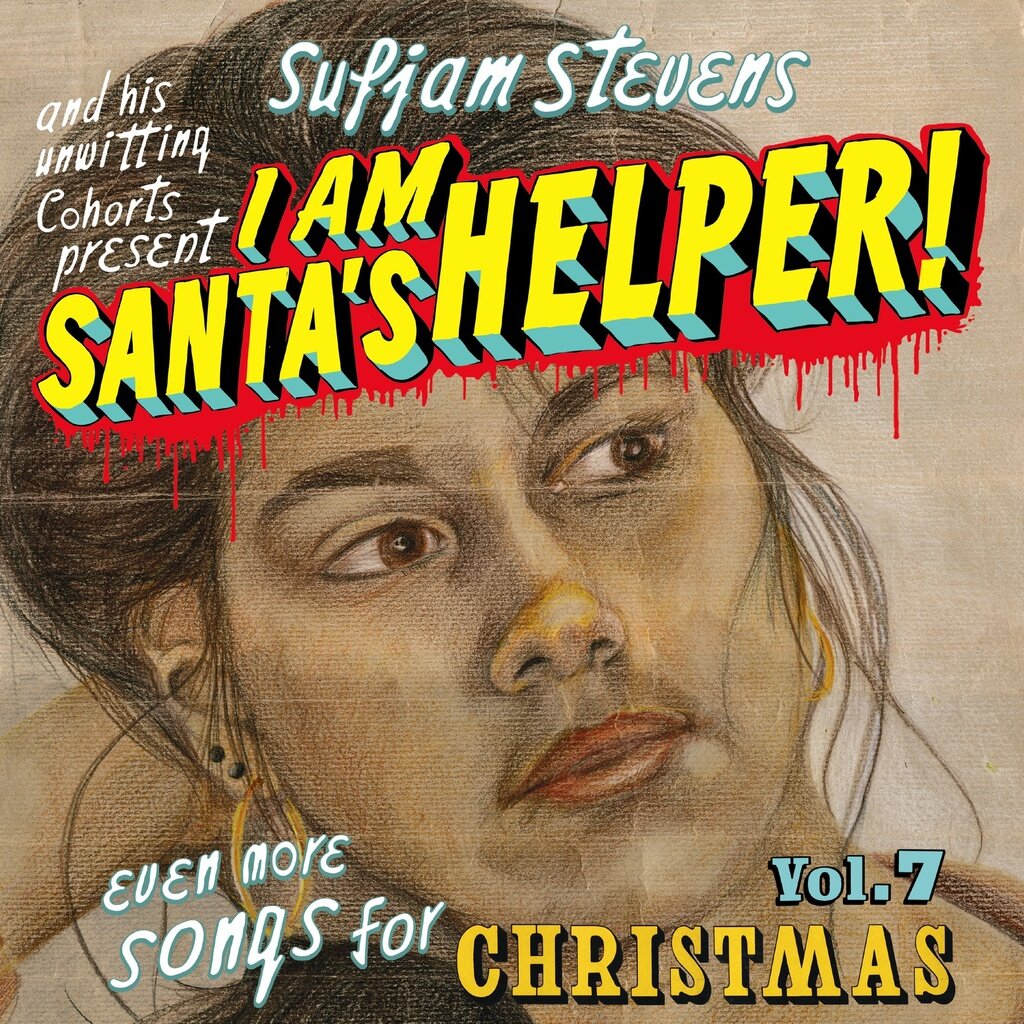

To everyone’s surprise, I attended a Catholic college in the northeast and was taught a different and radical perspective on faith. Through professors wiser than I’ll ever be, I learned that G-d cannot, in fact, be a white man, and that love and forgiveness are more holy than any ritual. Reluctantly, I began to discover G-d again, this time as a stand-in for Love. I started noticing G-d in my relationships, my peers’ devotion to justice, and the colors of the sky at sunset. At the same time, I also discovered Sufjan’s Christmas music.

***

The holiday season, despite my skepticism toward the Church’s teachings, has always invoked warmth and connection for me. This has often served to ground me in life’s more unpredictable times, as Christmas is a sensory experience in addition to a spiritual one. Christmas is the smell of chocolate and pine, the tinkle of bells, the softness of flannel pajamas. In my time at college, it was feeling snow crushed under my boots, flipping through pages in a quiet library, and a scarf pressed against my face. Sometimes, it was also the ringing of the hymns sung by a student choir.

Sufjan had already established himself as my favorite musician by this time, and in no small part because of his raw examination of faith and exploration of sexuality. His music held both anger at God and reverence for the scriptures, and I felt understood within that tension. I was delighted to find these themes explicitly present in his Christmas music, spanning genres and eras. However, I initially skipped over the many hymns sung throughout his second collection of songs, Silver and Gold.

I could not understand why Sufjan would choose to focus on the dry and lifeless hymns that represented this bleak and oppressive religion. I remember sneering at the different hymns and rolling my eyes at what I thought was a transparent attempt to be quirky (I mean, did we really need three different versions of “Ah Holy Jesus?”)

However, the more I fell in love with the eclectic songs on the record, the more strange I felt ignoring this part of the album. I decided one day to put my headphones in and just get it over with. I chose the first of these tracks - “Break Forth O Beauteous Heavenly Light,” a carol I had never heard before.

The song ended a little over a minute after it began, and I found myself going back and listening again. I kept hitting repeat, trying to make out the formal lyrics, becoming moved at the rising crescendo of the lyric “The power of Satan,” and the drawn-out lilt of “breaking.” I attempted to sing the different harmonies and work out the song’s message.

I had a similar experience with the other hymnal songs found on the second disc of Silver & Gold, even including the three different versions of “Ah Holy Jesus.” I couldn’t believe I was actually looking forward to the choral arrangements of songs I had never been able to relate to.

I remember first being struck by the quality of the recording itself; “Break Forth O Beauteous Heavenly Light” is a rather unpolished rendition of a definitively formal Catholic hymn. Sufjan and co.’s voices are warbly and slightly pitchy. The arrangement is haphazardly thrown together with a simple piano accompaniment, and seemingly performed without rehearsal. I had never before heard a recorded chorus or choir sound anything less than pristine, and I was captivated by how accessible this version was. It sounded like something I could hear in the pews at Mass.

While unfamiliar with this particular carol, its hopeful message framed by a melancholy melody was distinctly familiar to me as a former devotee of Catholic music. While in a major key, the music and lyrics still feel dissonant. At its core, it’s about the power of a new day, the promise of Christ’s birth, and the literal dawning of a new era.

In “Break Forth O Beauteous Heavenly Light,” the singers slowly and deliberately make their way through the limited lyrics. They distinctly pause between each sentiment, drawing breath before leaning into the next section of the reverential carol.

Regardless of intention, their singing serves as a personal reminder to have patience with the process of finding faith and finding G-d. I shouldn’t rush between moments and expect quick resolution to the crises that will inevitably come up. There’s a certain holiness found in these hushed breaths; they lend a sense of intimacy to what could be, and mostly is, a grand and distant canticle.

I listen to “Break Forth O Beauteous Heavenly Light,” and hear a small group of imperfect singers, led by a queer-adjacent man fraught with doubts, sing about the sanctity of light and hope. I have realized that I am allowed to access the beauty and grace that can still be found within the austere and oppressive traditions of the Catholic Church. I am entitled to question and mourn the joy I wasn’t allowed to express within the faith as a penitent child, and feel the elation that a savior has been born. “Break Forth O Beauteous Heavenly Light” represents the power of “confidence and joy” that can be found in song, no matter its origin. And I’m going to keep singing.

Written by Anne Williams (she/her)